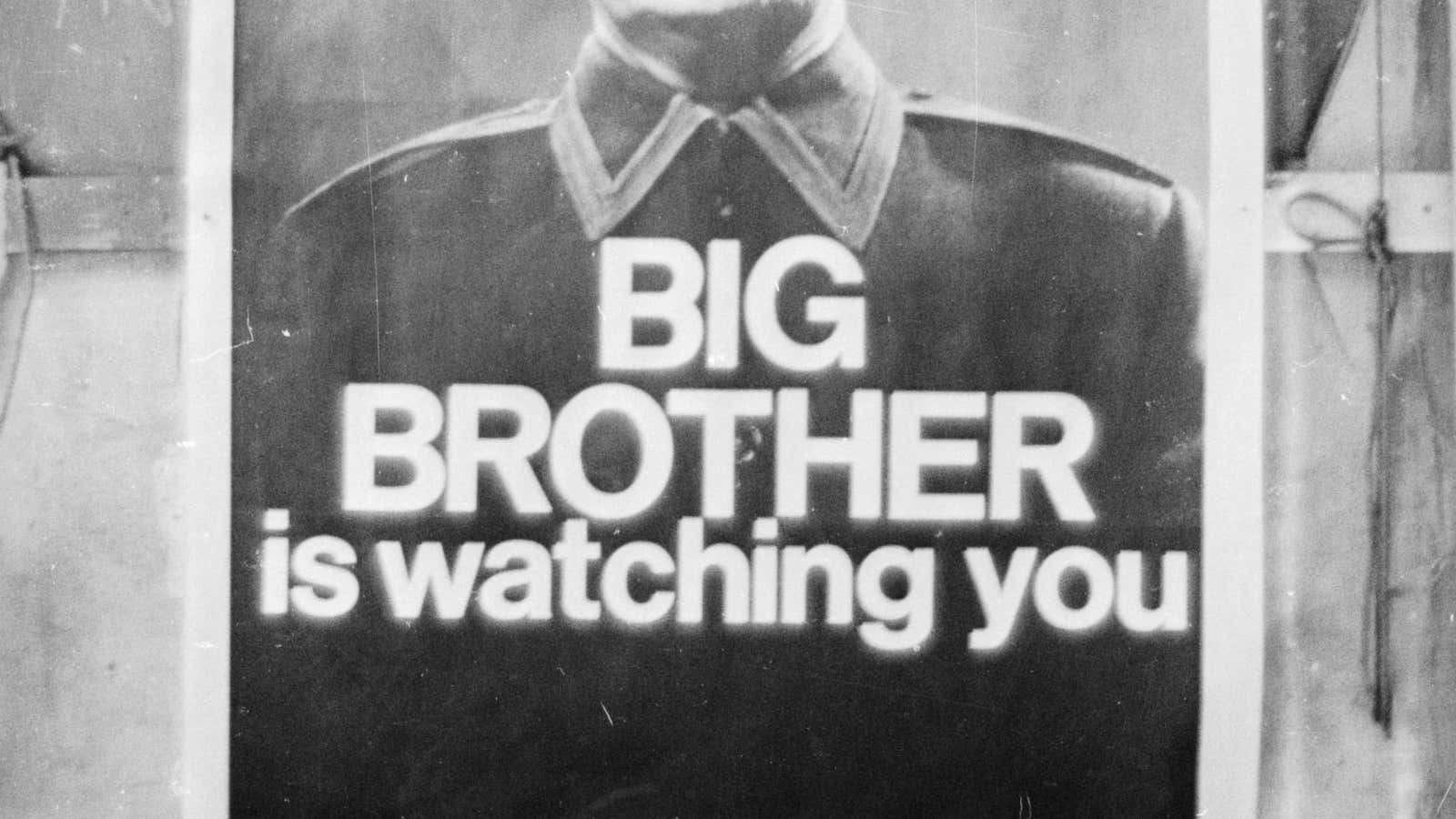

If there is any doubt about the persistent power of literature in the face of digital culture, it should be banished by the recent climb of George Orwell’s 1984 up the Amazon “Movers & Shakers” list. There is much that’s resonant for us in Orwell’s dystopia in the face of Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA: the totalitarian State of Oceania, its sinister Big Brother, always watching, the history-erasing Ministry of Truth, and the menacing Thought Police, with their omnipresent telescreens. All this may seem to be the endgame of indiscriminate data mining, surveillance, and duplicitous government control. We look to 1984 as a clear cautionary tale, even a prophecy, of systematic abuse of power taken to the end of the line. However, the notion that the novel concludes with a brainwashed, broken protagonist, Winston Smith, weeping into his Victory Gin and the bitter sentence: “He loved Big Brother,” are not exactly right. Big Brother does not actually get the last word.

After “THE END,” Orwell includes another chapter, an appendix, called “The Principles of Newspeak.” Since it has the trappings of a tedious scholarly treatise, readers often skip the appendix. But it changes our whole understanding of the novel. Written from some unspecified point in the future, it suggests that Big Brother was eventually defeated. The victory is attributed not to individual rebels or to The Brotherhood, an anonymous resistance group, but rather to language itself. The appendix details Oceania’s attempt to replace Oldspeak, or English, with Newspeak, a linguistic shorthand that reduces the world of ideas to a set of simple, stark words. “The whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought.” It will render dissent “literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it.”

But it never comes to pass. The Party’s plans—the abolition of the family, laughter, art, literature, curiosity, pleasure, in favor of a “boot stamping down on a human face forever”—are never achieved because Newspeak fails to take. Why? Because it was too difficult to translate Oldspeak literature into Newspeak. The text Orwell singles out to exemplify this, intriguingly, is the Declaration of Independence. The “author” of the appendix argues that these ideas cannot be expressed in Newspeak, specifically the part about governments deriving their legitimacy from the consent of the people, and citizens having the right to challenge any government that fails to honor the contract. As long as we have a nuanced, expansive system of language, Orwell claims, we will have freedom and the possibility of dissent.

This appeal to the integrity of language and principled thought may sound utopic or academic, but we are currently in the midst of a similar struggle. Consider the names of the post-9/11 programs that were ostensibly designed to protect the United States: the Patriot Act, Boundless Informant, and practices like “enhanced interrogation techniques.” The justifications of these 1984-sounding schemes—and PRISM too—follow the obfuscating principles of Newspeak and the kind of manipulative euphemism Orwell skewers in his famous essay, “Politics and the English Language.” He writes: “Political language—and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists—is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Orwell maintains that misleading terminology and evasive explanations are endemic to modern politics. “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible,” including practices like imprisoning people “for years without trial,“ Orwell writes.

If the main story of 1984 is language and freedom of thought, a crucial part of the Snowden case is technology as a conduit of ideas. In Orwell’s novel, technology is a purely oppressive force, but in reality it can also be a means of liberation. Snowden has claimed that tech companies are in collusion with the government, but he’s also using those same channels of technology to tell his story. Daniel Ellsberg had to photocopy the Pentagon Papers and distribute them in hard copies; now our language of dissent includes emails, tweets, and IMs.

It’s worth recalling Apple’s famous ad that unveiled the Macintosh computer to the world in 1984, making full use of the reference to Orwell’s novel. A mass of worker drones trudges toward a screen showing a bespectacled leader proclaiming that, “We have created, for the first time in all history, a garden of pure ideology—where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests purveying contradictory truths.” Suddenly, an athletic woman, in glorious technicolor, emerges with a hammer, the police in pursuit. She hurls the weapon at the screen and smashes the image. “On January 24th,” the screen tells us, “Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’” Apple’s Board of Directors tried to block the ad, but Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak pushed it through.

This is contemporary technology’s founding myth: the garage band ethos of its early founders going up against centralized, bureaucratic cultures like IBM by putting technology into the hands of the people. Obviously, scrappy startups have grown into multinational corporations led by wealthy CEOs, and most successful social networks are now run by powerful companies. However, we are surrounded by examples of technology used to question the status quo: Twitter and the Arab Spring is one example, Wikileaks is another, and so is Snowden.

When Orwell wrote 1984, he was responding to the Cold War, not contemporary terrorism. He did not anticipate the full reach of digital technology. Even so, he was correct in seeing a future where the government had greater control but also a belief in the people’s ability to use language for dissent.